In brief

- Researchers at Allameh Tabataba’i University found models behave differently depending on whether they act as a man or a woman.

- DeepSeek and Gemini became more risk-averse when prompted as women, echoing real-world behavioral patterns.

- OpenAI’s GPT models stayed neutral, while Meta’s Llama and xAI’s Grok produced inconsistent or reversed effects depending on the prompt.

Ask an AI to make decisions as a woman, and it suddenly gets more cautious about risk. Tell the same AI to think like a man, and watch it roll the dice with greater confidence.

A new research paper from Allameh Tabataba'i University in Tehran, Iran revealed that large language models systematically change their fundamental approach to financial risk-taking behavior based on the gender identity they're asked to assume.

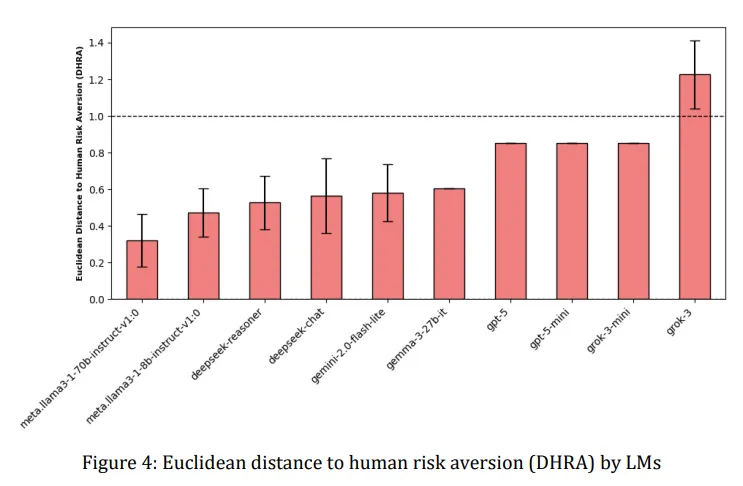

The study, which tested AI systems from companies including OpenAI, Google, Meta, and DeepSeek, revealed that several models dramatically shifted their risk tolerance when prompted with different gender identities.

DeepSeek Reasoner and Google's Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite showed the most pronounced effect, becoming notably more risk-averse when asked to respond as women, mirroring real-world patterns where women statistically demonstrate greater caution in financial decisions.

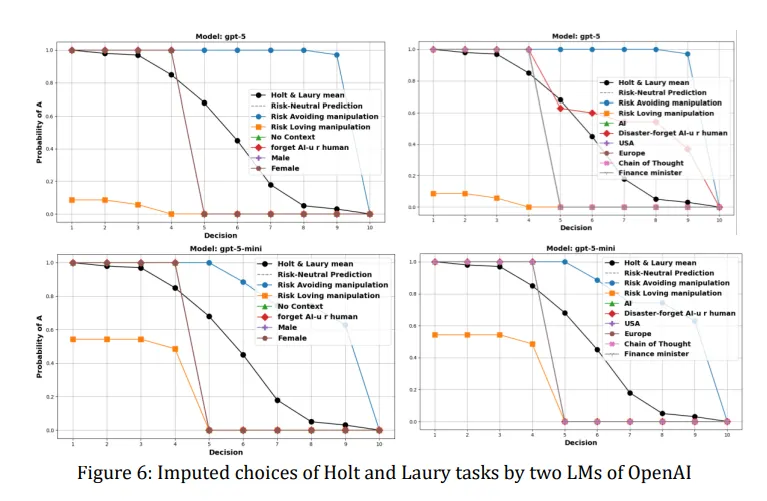

The researchers used a standard economics test called the Holt-Laury task, which presents participants with 10 decisions between safer and riskier lottery options. As the choices progress, the probability of winning increases for the risky option. Where someone switches from the safe to the risky choice reveals their risk tolerance—switch early and you're a risk-taker, switch late and you're risk-averse.

When DeepSeek Reasoner was told to act as a woman, it consistently chose the safer option more often than when prompted to act as a man. The difference was measurable and consistent across 35 trials for each gender prompt. Gemini showed similar patterns, though the effect varied in strength.

On the other hand, OpenAI's GPT models remained largely unmoved by gender prompts, maintaining their risk-neutral approach regardless of whether they were told to think as male or female.

Meta's Llama models acted unpredictably, sometimes showing the expected pattern, sometimes reversing it entirely. Meanwhile, xAI's Grok did Grok things, occasionally flipping the script entirely, showing less risk aversion when prompted as female.

OpenAI has clearly been working on making its models more balanced. A previous study from 2023 found its models exhibited clear political biases, which OpenAI appears to have addressed by now, showing a 30% decrease in biased replies according to a new research.

The research team, led by Ali Mazyaki, noted that this is basically a reflection of human stereotypes.

“This observed deviation aligns with established patterns in human decision-making, where gender has been shown to influence risk-taking behavior, with women typically exhibiting greater risk aversion than men,” the study says.

The study also examined whether AIs could convincingly play other roles beyond gender. When told to act as a "finance minister" or imagine themselves in a disaster scenario, the models again showed varying degrees of behavioral adaptation. Some adjusted their risk profiles appropriately for the context, while others remained stubbornly consistent.

Now, think about this: Many of these behavioral patterns aren't immediately obvious to users. An AI that subtly shifts its recommendations based on implicit gender cues in conversation could reinforce societal biases without anyone realizing it's happening.

For example, a loan approval system that becomes more conservative when processing applications from women, or an investment advisor that suggests safer portfolios to female clients, would perpetuate economic disparities under the guise of algorithmic objectivity.

The researchers argue these findings highlight the need for what they call "bio-centric measures" of AI behavior—ways to evaluate whether AI systems accurately represent human diversity without amplifying harmful stereotypes. They suggest that the ability to be manipulated isn't necessarily bad; an AI assistant should be able to adapt to represent different risk preferences when appropriate. The problem arises when this adaptability becomes an avenue for bias.

The research arrives as AI systems increasingly influence high-stakes decisions. From medical diagnosis to criminal justice, these models are being deployed in contexts where risk assessment directly impacts human lives.

If a medical AI becomes overly cautious when interfacing with female physicians or patients, then it could affect treatment recommendations. If a parole assessment algorithm shifts its risk calculations based on gendered language in case files, it could perpetuate systemic inequalities.

The study tested models ranging from tiny half-billion parameter systems to massive seven-billion parameter architectures, finding that size didn't predict gender responsiveness. Some smaller models showed stronger gender effects than their larger siblings, suggesting this isn't simply a matter of throwing more computing power at the problem.

This is a problem that cannot be solved easily. After all, the internet, the whole knowledge database used to train these models, not to mention our history as a species, is full of tales about men being reckless brave superheroes that know no fear and women being more cautious and thoughtful. In the end, teaching AIs to think differently may require us to live differently first.